The CEO of MediaScience, a lab studying marketing through neurology, talks with Colin Finkle about bring scientific rigor to branding.

Branding happens in the mind; our propensity to track reputations and use our experience with people and organizations to guide our future behaviour is all built into our neurology.

But brand builders, marketers and designers rarely think about what is going on “under the hood.” Psychology and neurology seem like too much parse when you are just trying to choose a headline that will convert.

But MediaScience is using scientific measures to make such decisions. They use experimental design and measurement of our biology to help large media platforms and companies make critical marketing decisions using scientifically gathered data.

For example, Dr Duane Varan and I talk about using response latency testing (RLT) to measure brand associations. This test measures how fast a subject responds with one thought after being primed with another. RLT is a way to test brand associations in a far more objective, quantifiable, and reliable method than traditional measures like surveys.

Before you think that such testing is excellent but entirely out of reach, prepare to be surprised. Brands, large and small, are looking for cheap, easy to run tests to get feedback on their brand. Technology is developing to perform tests with electronics as simple and small as a FitBit or Xbox Kinect. Therefore, Dr Varan’s tests in the lab today may be available to you tomorrow.

Companies that foster a culture of research and regularly test assumptions will have an advantage in building brands in the next hundred years.

Do you want to build your brand using the scientific method? Or are you happy playing guessing games?

If you are excited about the prospect, you will enjoy the conversation I (Colin Finkle) had with Dr Duane Varan.

Video

Remember to Subscibe to BMB on Youtube.

Transcript

Colin Finkle

I am here with Dr Duane Varan. Dr Varan, do you want to take us on a trip through your background?

Duane Varan

Sure. I graduated once upon a time. My PhD research was fascinating. I took these Islands in the Pacific that didn’t have television, and the government there was phasing on TV one island at a time. And so, I had the perfect natural experiment. And so eventually, one island received TV channels, and the other didn’t. And eventually, both Islands received TV channels.

That was the start of my career, and ever since then, I’ve loved experimental design. And so, everything that I’ve done ever since has been grounded in experimental design. Eventually, that took me into neuroscience as well.

I realized very early in my career that when we’re talking about media or marketing fundamentally, above all, we’re talking about human emotion. But the problem that we have is that people lack access to their own emotional journey.

You ask people about how they’re feeling about something or anything about their emotions. They’re telling you the rational interpretation of what they think they must be feeling, which is very different from what they’re really feeling. And so, I built my career around trying to measure that more directly.

And we’ve been very successful. I mean, both in my academic career and in business as well. And it’s just a much better way of looking at media and marketing research.

Colin Finkle

Yeah, for sure. We want to have as close to ground level truth and not be working on self-reports and assumptions.

So we always start with a question that is very short but very challenging. What does the term brand mean to you?

Duane Varan

To me, ‘brand’ is the real estate of the mind. If you think about any category, that category for any one individual, that category has a particular meaning. Specific associations are formed in their mind around that.

The question is, how much of that space do you as a brand occupy? And it’s one of the things that’s very deceptive about branding. You may have two brands, and one might have a 30% market share, and the other might have a 28% market share. And you might think, Oh, that’s not that much of a difference; the 30% is not that much better.

But, for most people, we don’t make our decisions around many brands. We tend to land on a brand and go with that brand in many categories. So it’s a question about being the leader, not about being second best, but about being in an individual’s mind.

So you might be thinking Coke has some of my mental real estate, but there’s not an equal or a semi equal probability that I’ll go with Coke or Pepsi at any time. I’m probably going to go with Coke.

So that’s an important nuance to it that it’s a leadership game. It’s not a game to be just a player or to have a share of that market. You want to own that space in a consumer’s mind.

Colin Finkle

Yeah, that sounds daunting, but you can define your niches narrowly as you want to. And if you’re the only person in people’s mind as far as that niche is concerned, then you’re in a market of one, and you can set your terms and do well by them.

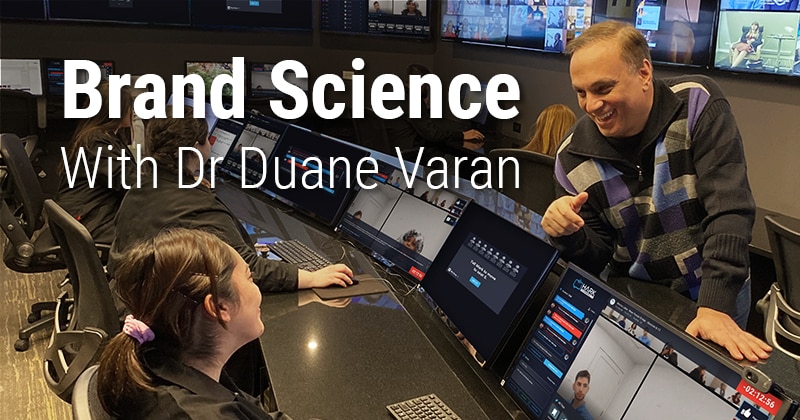

So you started MediaScience, which is a lab consulting for some big names. And can you tell us about MediaScience and what you guys test in there and why?

Duane Varan

Yeah. So MediaScience is the leader in the market in terms of testing ad innovation. So just about any significant ad innovation you can think of in the industry was first studied at MediaScience. So picture-in-picture advertising, six-second ads, limited interruption advertising, the choice model for ads, interactive… Just about every interactive thing you can imagine. All of these things were first tested at Media Science. Pretty much every major TV network group is a client of ours, many global brands, many social media firms.

That’s certainly where we shine, particularly because of our capabilities. We have a very deep toolbox. We pretty much have every tool under the sun at our disposal in terms of studying. And what we tend to do is look at a problem and find the best-in-class method for studying it.

We’re boutique. We’re not the largest player. We don’t have big global conglomerates as our shareholders; we’re nimble. But we have an exciting business. We think of ourselves more as a movement; we’re a movement really about responding to the changing landscape.

Colin Finkle

I appreciate the work that you’re doing because the traditional media was so dominant for so long, these video forms of advertising.

With over the top and some other ways of being more nimble on their side, the question is: how does the traditional media guy come in with numbers? Whereas the digital media marketer has all these stats and figures around their KPIs. You guys sound like you’re bringing some hard data to stuff that’s been traditionally hard to quantify.

Duane Varan

That’s true. With new formats, there’s a gap. It’s not like you can rely on ratings for a new format. And so everybody in the market needs to have some sense of efficacy.

At the front end, we do the research that provides that kind of data. And then, later on, we provide the evaluative work. That kind of talks about an individual campaign and how it’s performed, particularly in those new lanes where there aren’t common currencies in the market yet.

So that’s certainly a lot of what we do. Of course, we do other things as well. We do program research, pilot testing. So we have a pretty broad remit in those spaces.

Colin Finkle

Yeah, I’m sure there are CMOs out there that are used to digital advertising, where they have reports and reports of data, and then they’re tracking conversions, and they think, “then who needs to test? Let’s just see our conversions or sales are affected; let that be the test.”

Is testing purely with sales and conversions dangerous?

Duane Varan

Yeah. So incrementalism has its place. It’s suitable for optimizing. So when you have a strategy, or you’re deploying your strategy, you really want to optimize.

But a brand needs to know what it’s doing, not just see the end results, but understand the moving parts. And the problem with incrementalism is you don’t understand the moving parts. You don’t know the why behind things that you see. You end up making assumptions, and those assumptions can be very dangerous.

So what you want is you want the empirical evidence which answers the why. In other words, you don’t want it to be a gut feel thing. You want solid evidence, which tells you why in many ways.

The question that you’re asking is a many centuries old question. It’s the battle between Aristotelian science and Galilean science, empirical science and analytical science.

The way that Aristotle made sense out of the world was by observation and by categorization. And so he would, for example, if he wanted to classify creatures, he would say: “creatures that fly, creatures that are on land, creatures that are in the sea.” And he’d come up with subcategories, and every observation goes in a bucket.

And as a result, you end up with all kinds of assumptions about how you think things work. So, for example, one of those was about heavy objects falling faster because you observe that heavy objects must be falling faster than light objects.

But of course, Galileo came along with a very different paradigm of science, and this paradigm is based on variables and isolating variables to understand their effect.

Galileo approached that same question about heavy versus light objects in a different way. What he did to isolate the variable was to create two ramps. (The story is usually told around the Leaning Tower of Pisa, which is, of course, fiction.) It was these ramps that he rolled them down, and then he built these ramps, two balls identical in every way. One is heavier than the other, same shape, same volume, same surface material. Just one is heavier than the other. And then what he did is he put bells along the way on the ramp. So as the ball rolls down, the bells chime. Then he releases the two, and he sees them chime at the same time.

So that assumption that was behind Aristotle’s observations was flawed. The only way to get to that level of why is with empirical science, which is grounded in experimental design because of that ability to isolate a variable and adequately measure it.

So what brands should be doing rather than just the incremental thing, which is a tactical response, is they should be very clear about their communication objectives. And for each objective, they should have the best-in-class measure to make sure that they properly understand how that particular variable is performing across creative executions.

And that’s the kind of game that we engage in at MediaScience. It’s not in competition with the kind of incrementalism and tactical research you’re talking about, but it helps inform it. So it’s part of the puzzle.

Colin Finkle

Yeah, marketers are not known for wanting our hunches to be disproven or assumptions to be challenged. How do we become more scientific as a group, us brand marketers?

Duane Varan

Well, you’re right in that the commitment to a scientific approach inherently means that it has to be falsifiable, and that means that you have to be proud that you have the opportunity to say to your client: “this doesn’t work. You’re not getting the results you thought you were getting. Your competition is doing better than you.”

This is why the empirical approach is so much more powerful because it answers ‘the why’ and not just ‘the what.’

You can look at something that fails, and you can understand why it fails. And in that context, what you’re able to do is not just go back with bad news but also with bad news and potential solutions.

If all you were doing was being the bearer of bad news, well, you know what’s the marketers are going to do with that? All you do is just make them look bad.

But if you go back with bad news and with the potential for a solution to that, to be fair, is going to require more testing. That’s the nature of the beast, but at least you’re not wasting your money with something that’s going to fail in the market ultimately.

You’re instead learning from that failure and potentially getting to a solution that is far more likely to work in the marketplace. That’s the nature of that kind of challenge.

Colin Finkle

I never thought about the difference between having some insight on the why versus just iteratively looking at your sales data. That presents itself with solutions when you know the why. When you see the numbers on the wrong trajectory, that doesn’t tell you what’s going on.

Duane Varan

You don’t know what’s going on. You’re making assumptions about it, which could be wrong.

I’ll give you a great example of this. We looked at one of the big projects that we did. We analyzed all of the interactive TV data that was coming out of a major UK provider. And we analyzed the state, the response data, the clicks, basically for a connected TV-style environment. We analyzed the clicks, and they had observed that a lot of their best performing cases were cases where people had clicked for more information.

But what we discovered through our methods was that that request for more information was the kiss of death. That request for more information drove the response down -470%. It was just about the worst thing you could do.

Now it happens that many of these star performers did it, but they succeeded despite that, not because of that. And their superstar performance created the misperception that was happening because of that call to action that said click for more information.

Only with the power of experimental design do you get at what’s going on and what drives an effect, instead of anecdotally what you think might be going on, which is, again, very dangerous, potentially.

Colin Finkle

Yeah. It makes me think of the nature of assumptions; we can’t execute on anything if we’re down to zero assumptions; we’re always making assumptions. But just being aware of those assumptions, aware that assumptions are being made and that if you have the opportunity to disprove them, that you invite that opportunity, then you’ll be okay.

Duane Varan

Well, what’s important for us to remember is what it used to be like in the marketing industry. We could get by on some assumptions because we had 50 years of experience with the medium; yesterday looked exactly like tomorrow. A 30-second commercial was a 30-second commercial, and that didn’t change much over time. We were working with the same ad format.

But now we don’t live in that kind of world. Now we live in a world of perpetual change, and we’re constantly dealing with things for which we have no experience. And so we don’t have the kind of experience which informs our gut feel, ultimately. It’s much more dangerous today to be relying on those assumptions that it might have been 10 or 20 years ago.

Colin Finkle

Yeah, for sure. If you’re on the highway on a rainstorm and your visibility gets limited, what do you do? You slow down.

Well, people in marketing were used to a much slower environment. Now they have to go with the speed of traffic, so we have to get those windshield wipers going and see the way in front of us.

Duane Varan

Research is the remedy to the unknown. So if we don’t know, we better research to figure it out.

Colin Finkle

Yeah: get some more data.

So on that topic: neuromarketing associated with a lab environment. It can be hard to get participants into the lab; you have to pay them something. And there’s all the equipment; I’m sure that has quite a price tag.

Is neuro measures testing getting a little more accessible now? I’m sure technology is solving some of these problems.

Duane Varan

Yeah, it’s a lot more accessible than it’s been, certainly. The most accessible is facial coding: the analysis of muscle movement on the face, which can be done with a webcam. So that does not require sophisticated technology. People who are born blind at birth display exactly the same facial gestures as everybody else. Your emotion is hardwired to your face. And so seeing a person’s reaction and mapping the muscles on the face and trying to codify them: that’s a very powerful neuromarketing tool that is both inexpensive and readily available.

So that’s a great example. And it didn’t use to be like that. Ten years ago, when I was doing facial coding research, we used facial electromyography, which was wires on the face. So we’ve gone from something that was fairly intrusive to something entirely natural and relatively inexpensive. Another area where we see some real progress is in at-home home neuro measures. We have deployed a panel, for example, where we measure people for their galvanic skin response and their heart rate in their homes.

And even now, it’s still a little bit expensive because we have to mail it to people and the kits are very expensive. But it will get to a point where you will be able to use sensory devices on people’s wrists, the equivalent of a Fitbit that people already have to get data. It’s not what I would call reliable yet. We still have a path to improving a lot of the quality of those measures, but we’ll get there, we’re getting there. Those measures and the algorithms behind them are constantly getting better.

And so I do think that this is something that becomes more and more accessible and more natural and more available over time, for sure.

Colin Finkle

Yeah, I’m sure as those data capturing devices are getting less intrusive and closer to the environment that people are watching ads in, so the data becomes even better. There is an excellent convergence there.

Duane Varan

And some technologies won’t become accessible. I wouldn’t expect to see EEG or fMRI or anything that’s doing any serious brain imaging, for example, at home. But we are of a school that those particular measures, the data that you need from those can be collected through less invasive ways.

So, for example, we recently did an excellent study for Google in collaboration with the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute. And we demonstrated that heart rate, for example, was just as good as EEG in measuring for attention.

And so, again, this is becoming more accessible because before, people would have thought that to get reliable measures of attention, you needed a complete EEG kit. Obviously, that’s going to be a lab-based challenge for a long time still. But if it’s heart rate again, a Fitbit can give you that and reliably give you that. So, again, we’re moving into some exciting future possibilities around that.

Colin Finkle

You have a unique view of marketing tactics with all the testing that you’ve done for all your clients. The readers and writers at Brand Marketing Blog believe that the fundamentals of branding are true, but they are assumptions.

We assume that building a reputation helps sell products. When you scrutinize that with neuroscience and behavioral data, does that assumption hold up? What is the role of brands when you’re testing?

Duane Varan

Well, absolutely. Everything that we do shows differences, not only differences by brand, but other subtle things, like where an ad is placed and what is in the environment around the ad, what the format is; all of these things matter.

So all of the fundamental laws of branding apply. Without branding you’re a commodity, and you live or die just on the product itself. But the customer doesn’t get the added value of a strong brand if that is the case. That’s what the brand ultimately brings.

So there’s no question that the classic rules of branding always apply. There’s a lot more that we’re learning, and we’re going a lot deeper in understanding how branding works. But indeed, the fundamentals were true before, and they continue to be true going forward.

Colin Finkle

That’s good to hear.

As you said, the brands live in the mind. So with neuroscience, there is a way into the mind and understand that. So I’m sure we’ll see more testing than in the decades past, and I’m people testing their brand will have certain advantages.

Duane Varan

Let me just give you an example to illustrate that. Historically, we know that attention matters. Good research was done long ago and has always demonstrated this peculiar problem: low attention can also lead to high sales.

And this has created something that has confused marketers for many decades; we assume that attention is a good thing. Why is it then that low attention also does well? This kind of doesn’t make sense, right?

Well using neuroscience has helped solve that mystery. And what we’ve discovered. Again, this is the work I talked about earlier done for Google and collaboration with the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute. And what we found was that people have been conceptualizing attention wrong and not just in on this marketing question, but across the board.

We’ve been conceptualizing attention wrong when we study driver fatigue and things like that, because we always think of it as a continuum. And if you have a little bit of attention, that’s good, but more attention, that’d be even better, and that just does not hold and stack up to the data.

And the reason is: attention doesn’t work that way. Attention is a threshold. And if you get above the threshold, you have your foot in the door, and then it’s up to other things to deliver the impact.

So really, we’re thinking about it wrong. We shouldn’t be talking about attention. We should be talking about inattention. In fact, the way we now define attention at MediaScience is the lack of inattention. And we can reliably measure for inattention. And if you don’t have an inattention, you’ve crossed that threshold, and above that threshold, it’s about a whole bunch of other measures and how they fly.

So attention is just a threshold. Once you’re past that threshold, there’s no added benefit in being a little bit more, a little bit less. It’s just that you’re paying attention now, so it’s about all the rest of the things that have to trigger in. Again it’s just an example of this point that these tools are helping us understand these classic ideas, these classic principles, much, much better than we’ve been able to know in the past because we can now measure them.

Colin Finkle

That makes absolute sense to me. I always think of branding as a heuristic that people use if their capacity for attention is low.

For example, if you’re going to the grocery store and you’ve got some time to pick the right protein powder, then you might be in there reading labels and whatnot. But that’s not the world we live in much of the time. When people have to go about their lives, and they can only give limited attention to their purchases

What do customers fall back on when their attention is limited? Brands! Do I trust this brand? If yes, then in the cart it goes.

It makes absolute sense to me that branding would live in a space where attention is limited.

Duane Varan

Yeah, that’s right. And because of that, that’s where the primary value proposition lies. If you’re looking at a pair of shoes, the shoes cost might sell for $130, and the manufacturing of it and the shipping of it and everything might be $20 of that $130. The rest of the cost is the branding because the brand is why one pair of shoes is going to sell over the other pair of shoes.

In some industries, a strong brand is not just delivering an incremental value; it’s providing the lion’s share of the value, so branding is a big deal at the end of the day.

Colin Finkle

Yeah. Again, I relate to that, too. I have this battle in my mind where I know that there are people that are critical of branding, believing it to be some sort of mind game.

But if somebody has a car, and because they have complete trust in whatever brand of car it is, and the experience of the car is just full of ease, it just works, and they’re happy with it. Who’s to say that isn’t real value?

Who’s to say that improvement on the perception of the product isn’t real?

Duane Varan

Yeah. It’s a good point because we need to recognize that it would not be a better world if we lived in a world without brands. It would be a worse world.

Brands invest, and that investment gives us a better product continuously. And that would not be the case if we were trading ultimately on a commodity. So we live in a better world because of brands, not a worse world, for sure.

Colin Finkle

Yeah, you’re preaching the choir with that.

Can brand identities be validated with neuroscience? Can we look at some objective measures during a company’s rebranding? Can we test if one look will work better with the customer than another look?

Duane Varan

Yeah, absolutely.

I remember one study that we did for ESPN. And it wasn’t an ad; it was a promo. ESPN was promoting a basketball program, and we looked at a single word. We were trying to understand the impact of a single word.

It was an AB test essentially, but we had the power of many tools. We had the power of eye-tracking. We had the power of the biometric measures to look at how people reacted and how they were responding.

And the only difference was whether the word said “Watch on Thursday” or whether it said, “Watch Tomorrow.”

The word tomorrow is a very arousing word. It’s a very exciting word. So what we discovered was that using the word tomorrow significantly improved memory. But more importantly, it changed the way that viewers experienced the promo. So they were much more excited when they saw the promo because it was tomorrow.

Of course, with this kind of AB testing combined with the power of experimental design, you can test anything. You can test music. You can test color. You can test absolutely anything. You can test every little nuance that is there to understand its effect.

So you’re right. It’s very powerful. One of the things on the creative side that’s been very frustrating for creatives historically is coming into a process where they don’t feel that their objectives are reflected in what they hear from the researchers.

The classic story is: you produce this ad, and you think it’s great. Then you get these research people to come and tell you: “it didn’t test well.” All of that is speaking a language that is very foreign to you. You’re getting some results which that are about the effect ultimately. But that’s not what you care about as a creative.

However, imagine, by way of contrast, that what you were hearing and what you’re being told is actually about your creative objectives. You thought you were making people laugh. But guess what? The joke wasn’t funny. People didn’t laugh when they saw that. That speaks to you as a creative. It speaks to your objective, not the overall marketing objective, not the objective that the suits have. How does research help me with my objective as a creative in terms of what I was trying to do emotionally with my message? So now you have measures that speak specifically to the goals that the creatives care about.

Another study we did for ESPN was helping this on-camera talent who was very, very difficult, and who hated research and not very receptive to feedback. They had this segment where they talked about racism in sports, and it was it had a little bit of a political tone to it, which people generally don’t like in the sports context.

The creatives thought it was great. They thought they were doing a fantastic job. We showed them the data; we showed them the data among African American viewers and white viewers. And for everybody, this was a huge turnoff.

But what was more important to the show’s talent was the change in how the audience experienced the rest of the episode. So once the audience had that sour taste in their mouth, they could not experience the rest of the show in the same way. So that spoke to him (the talent) in his language, and he responded well to the research because it was speaking to his objective.

So, these measures are powerful on the creative front because they speak to the objectives that matter most to creatives.

Colin Finkle

Yeah, I agree. I always thought inviting creatives into the testing environment would be effective. Whereas most agencies factory line creatives; “pump this out and then go on to banner ad 14 out of 19.” As a result, they stay at their desks instead of getting some feedback from the testing environment.

I listened to photography podcasts in the early 2000s when digital cameras were coming into the market. The photographers on the podcast explained how people who had never shot on anything but digital were getting so much better than the film photographers so quickly. This accelerated improvement was because a digital photographer took a picture and then looked at the picture to see how good it turned out. They repeated that process thousands of times a session, and the feedback loop was so tight that they improved rapidly.

Whereas on the creative side, we expect nice creativity from people and then the feedback is either delayed or never comes at all.

If there’s a loop between the people who produce pieces of creativity and then get to see how those pieces are working, you’re just going to develop better people and more effective people quickly.

So another thing I wanted to talk to you about was brand associations. Obviously, some prominent brand associations have lots of investment, such as Nike with athleticism or Volvo with safety. But I’m sure there’s a lot of subtle brand associations that are not as easily understood.

Are there ways of testing to see if these brand associations are sticking in the customers mind?

Duane Varan

Yeah, for sure. So one of the most common tools used is response latency testing.

For background, if you hold an association, then you will respond faster to it than if you don’t hold the association. You can measure the speed of people responding to testing a particular association. That is response latency testing in a nutshell.

There are strengths and weaknesses to the methodology. Generally, we find that it’s a powerful methodology where you have something going on that people may not be willing or able to articulate. Say if you’re dealing with gender roles, if you’re dealing with race, those are areas that need response latency because there’s no other way of kind of getting under the hood, so to speak. To see what’s happening under a person’s consciousness, under a person’s awareness, because they’re not generally aware that those issues are there for them.

We find that most associations are held at the surface. And so you can use a variety of more traditional techniques.

The easiest thing to do in terms of not necessarily relying on neuro methods is just a discrete choice analysis: giving people a variety of paired choices and understanding their decisions to kind of a tease through the associations they hold. And again, because most of those are going to be very much conscious associations that they’re holding, then that those methods will work.

But anytime you have something happening that you think may elicit an elusive response on a participant’s part, you have to resort to going to response latency testing.

Colin Finkle

Yeah. My understanding of response latency testing is that if you conjure a brand or any sort of cognitive category that things that are associated with that are sort of ready to fire in your mind in that thoughts or actions or responses will happen faster between concepts that are associated. Am I correct?

Duane Varan

Yeah, that’s exactly right. That’s the fundamental premise that it’s effectively primed by the association.

So if you were to say Volvo and Safety (“is a Volvo safe?”), you would expect that people would respond faster to that association, then they would respond if you said: “is a Volkswagen safe?” They’d have to think a little bit longer about that and say, is the Volkswagen safe?

That speed of their response is reflective of an association that they hold.

Colin Finkle

Yeah. That’s got to be extremely powerful for brand managers because there might be associations working and you want to double down on, or there may be negative associations. That maybe you don’t want to be associated with “discount” or whatever.

Duane Varan

Yeah. It’s an excellent point.

Response latent testing is a great tool for looking at negatives because people generally have a social desirability bias, and so they won’t want to tell you a lot of the negatives necessarily. They want to get invited to participate in the next survey or whatever. So oftentimes, you have a bias that’s reflected through that and response latency looks beyond that.

So you’re right. It’s a good tool for negative associations as well as positive.

Colin Finkle

Yeah. What a nice map that would give to the brand managers who are trying to navigate the next ten years of some of these brands.

Now, what we’ve talked about is useful for established brands, but I know that many people who come to the blog are smaller players that may not have the budgets or may not be making million-dollar decisions. I imagine that it would be silly to test a social media post, but if you’re doing a Super Bowl commercial, it would be silly not to test that. How and where do you think the line is?

How do you help people determine where the line of what we should test and what we shouldn’t test? How do you figure that?

Duane Varan

And you’re also right. It’s not just the small marketer who needs a lower budget solution.

The large marketer doesn’t only have the tent pole studies. They often need their day-to-day studies as well. They need the constant evaluative work that needs to happen, and that also needs to be more cost-effective.

So we have deep studies with many tools like eye-tracking, biometrics, etc., the suite of lab-based neuromarketing tools.

But you also have some that are not as deep but still give us a lot of information. Some of the ones that we have there are accessible to even small marketers, such as an over-the-top (OTT) channel that we at MediaScience launched ourselves. It’s our own private Netflix if you will. Our MediaScience channel.

The reason that we use the channel is because it allows us to properly AB test things. We have a lot of different skins, so we can make it look like it’s a Hulu experience or a Peacock experience or an HBO Max experience or whomever we need to make it look like one of the tools that we have there that’s great for a low budget marketer is we have built-in dial testing.

So we have a tool that we’ve built in where you can use the keys on your remote control to indicate your response second by second to what you’re seeing. And so it’s a proxy. It’s not as good, but it still gives us a little bit of detail, like on a continuous basis, second by second in terms of how people respond to the content. So that’s a nice, relatively inexpensive tool that’s available to the market.

And then, of course, the other tool is focus groups. Focus groups have been around forever. We’ve launched a division of MediaScience, which we call “HARK Connect.” And what we have determined to do for HARK Connect is to bring our full range of tools to make it accessible and available to the qual research industry. And what’s great about HARK Connect as well is we’re using, and we’ve built many AI tools to help people, so that effectively you have a virtual assistant who’s there sitting by your side during the session, and that virtual assistant we call her Ava. Ava is actually coding content.

Did somebody just say that word? Ava will code it. She can translate into over 60 languages in real-time. So you could see your session, or your client and Germany can see the session in German.

The editing tools are really powerful, so you can go in and extract. There’s sentiment analysis, which is looking at the word and classifying whether they’re positive or negative. And we have biometric tools that we’re bringing into the mix gradually.

So we’re trying to make a lot of those tools, algorithms, technologies accessible. Even at a very small level, for qualitative research, for the people who do the day-to-day bread and butter research around focus groups and in-depth interviews and things like that.

Colin Finkle

So it makes me think about the question; maybe it’s not a hard line between testing and no testing. There’s figuring out what test and what is appropriate, and there will be fidelity differences between those tests. But getting some data involved is always a good thing.

Duane Varan

Yeah. The bigger challenge is not about a study or a method. I think the bigger challenge is developing a culture.

To succeed as a brand, you need different ingredients, and particularly because of the level of change in the market today, one of those ingredients has to be research.

You have to have a culture of research. And that that culture needs to be based on substance and quality. There’s no point in having bad research. Bad research is worse than no research because it leads you astray. So you want good quality research.

Of course, you’re going to have budgetary constraints. So you have to figure out how to develop the culture of research within your means. And there are ways of doing that.

But I do think that the bigger challenge is the challenge of having the right culture. And if you don’t have that, you will be at the mercy of the elements. You might succeed, but it’s kind of haphazard whether you succeed or fail… ultimately.

Colin Finkle

Yeah. I agree.

In branding, we have a huge selection bias in that we see what the brand leaders are doing. Apple is perennially the example here, and we say they sowed decisively say: “We are doing this, and this is what is going out.” But they may have come up with 100 ideas, put them up to scrutiny, and then the only one you’re seeing is the one that they’re 100% confident in.

But small business owners say: “I have to be decisive. I have to make a decision and stand by it.” And that’s true. Maybe on a go-to-market strategy. But prior to that, you should become up with ideas and throwing them out as much as you can.

Duane Varan

Yeah. I don’t know if that’s quite the Apple example, but certainly, it would be Proctor and Gamble or Mars. I mean, many brands would be learning through failure as well.

But you’re right. We can’t commit to something if we don’t know whether it works. We need to have a few kinds of arrows in our quiver to pull the right one out, the one that’s most likely to ultimately succeed.

So the investment that we make… I mean, it’s a form of insurance. We want to back the winner. We want to back not just the winner generically the winner for our brand, the winner for our objectives. So not all formats are going to be equal. Not all environments are equal. We need to find the ones that are optimal for us. And the investment that we make and getting that right will repay itself a thousand times over because it saves waste in other environments.

Colin Finkle

Well, thank you so much for your time today, Dr Varan. I really appreciate it. I have one last question: is there any advice you want to leave the brand builders out there with that will help them?

Duane Varan

The only advice? It’s something that I said before. Don’t expect to go into an environment that is constantly changing with gut feel, with instinct.

You need to have research to guide you through the changing landscape. It’s critical. However it is, you go about doing it: that’s fine. But just make sure that there’s some process there for guiding you through those challenges.

Colin Finkle

Yeah. So coming back to that culture research. Well, thank you so much. I really appreciate it. And I’m sure we’ll be talking again soon.

Duane Varan

That was tons of fun. Thanks.

Leave a Reply