How companies use Brand Architecture to organize their brands.

‘What products should be marketed under what brands’ is a curious question. Why is Sprite a distinctly different brand than Coca-Cola? Why does General Motors sell four different mid-sized SUVs under four different brands? (Chevrolet, Buick, GMC, and Cadillac.)

There is logic used to tie together the diverse products sold by these enormous companies. The sorting of products into brands is no accident; it takes sophisticated marketing thinking to decide the boundaries and relationships between brands.

One tool CEOs, CMOs, and brand managers use to structure their thinking is brand architecture.

Brand architecture is the structure a business define uses to organize their offerings into brands that become meaningful to customers. A company’s brand architecture specifies which names, logos, messaging to apply to new and existing products.

Brands owned by the same company can be independent or related. One brand can endorse another (i.e., 3M Scotchgard), or a sub-brand can have greater specificity than its parent brand (i.e., Samsung Galaxy for touchscreen phones and tablets.) The parent company’s name can be used to market the product or left out entirely.

There are great benefits to implementing a smart brand architecture. A product marketed under the right brand can be successful and achieve product-market fit, increase sales, and reinforce the brand’s meaning in customers’ minds.

If brands are not organized effectively, and products are branded haphazardly, then the brands start to lose their meaning. We call this loss of meaning brand dilution.

Mis-branded products also confuse the marketplace and depress sales. Without a defined brand architecture, a brand might start selling a product they have no business selling, or brands of the same company can have so much overlap that they begin to work against one another.

For example, Dyson could be more thoughtful about their brand architecture. Here on BMB, we discussed how Dyson started selling lighting products when James Dyson purchased his son’s company in 2015. We concluded that lighting products should be sold under a different brand because the Dyson brand is associated with moving air (vacuum cleaners, hairdryers, air purifiers, etc.)

How do you build a brand architecture?

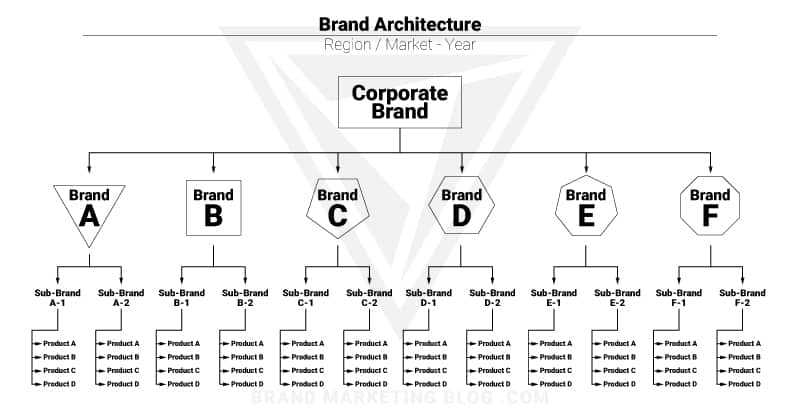

You understand your company’s brand architecture by organizing every brand in a branching hierarchy.

The goal of defining a brand architecture is to determine which names, logos, messaging to apply to new and existing products. Brands can be delineated by their product type, vertical market, customer base, or even styles and flavors; usually, the achitecture is a combination of all of these factors.

All the brands in a company’s portfolio need to be represented in the brand architecture: corporate brand, brands, sub-brands, technology brands, and unique product names. The relationships between all of these brands need to be defined. Are they independent? Is a brand the sub-brand of a parent brand? Can or should a term applied to one brand be applied to another?

The most helpful and straightforward way of defining these relationships is with a visual diagram; a tree diagram works well. Most relationships between brands become self-evident when arranged in a tree diagram.

A company’s brand architecture diagram will look like a family tree. There will always be one node at the top of the diagram (the corporation), and brands will branch off from there, and there may be hundreds of offerings on the bottom.

Horizontally (left to right), the diagram is organized by vertical market. If two brands are in a similar market, then they should be beside each other. For example, Lays, Doritos, and Ruffles should be adjacent in Pepsico‘s brand architecture diagram because they are all flavored potato chips.

Vertically (top to bottom), the diagram should define parent/child relationships. Brands that are broadly defined are on top, and brands that are nested within other brands fall below. For example, a branch below the Google brand would be Google Workspace, and a branch below that would be Google Docs.

The top to bottom hierarchy should have these steps:

Company -> Brands -> Sub-Brands -> Product Lines -> Products -> Product Variations

You can divide the offering at any level if it makes sense for the market. A brand manager may need to break up the product lines into multiple sub-brands if the differences need to be communicated and emphasized.

Brand architecture makes sense to do on a regional basis, usually by country. A brand architecture schema should make it easier is to understand what products and services would make sense to be offered under what brand. Large companies may have brands that do business in other countries but not in others. There is no point for a marketer or executive to include a foreign brand in the brand architecture because they don’t work with it and customers in their region aren’t aware of it.

For example, Unilever has a soap brand, Lux, which has become quite successful in Southeast Asia but is not actively marketed in North America. Soaps like Dove occupy a similar spot in the North American market.

BMB talked about Lux when we discussed examples of line extensions.

The CMO at Unilever USA should leave Lux out of anything outlining Unilever’s brand architecture because American customers are not aware of it. Marketers at Unilever won’t be working with it.

Examples of Brand Architecture

Understanding the organization of brands by looking at the brand architecture diagrams of various companies.

The best way to understand brand architecture is to look at and dissect brand architecture diagrams of well-known companies. You will start to get an intuitive sense of the relationships involved.

Coca-Cola

The Coca-Cola Company has many brands and competes in many different verticals. Their business is all about beverages but spans from sugary sodas (like Fanta) to milk fortified with protein for after workouts (Fairlife Core Power.)

The below diagram lays out all of Coca-Cola’s brands in a hierarchy and outlines its brand architecture.

Interestingly, Coca-Cola has multiple brands in the same category. For example, Nestea, Gold Peak Tea, and Peace Tea all serve iced-tea, but their brand personality, brand promise, and taste speak to different demographics with different values.

The relationship between Coca-Cola and Diet Coke is interesting. Diet Coke was marketed as a sub-brand of Coca-Cola for decades. I placed it as an independent brand because the corporation is trying to distance Diet Coke and Coca-Cola Zero Sugar mainly through the cans’ design, which look quite different. They are both no-calorie colas; Coca-Cola Zero Sugar tastes nearly the same as classic Coca-Cola, but Diet Coke has a light flavor, which some people prefer.

Volkswagen

Most consumers think of Volkswagen as relatively straightforward, practical, and plain. But the Volkswagen Auto Group is full of intrigue and style; sure, Volkswagen has the buttoned-up German brands like VW, Audi, and Porsche, but they also have chic, Italian brands such as Lamborghini and Ducati.

Note that there is another tier to the Volkswagen brand architecture that I left out of the figure: model designations.

All the brands have brands to denote what level of performance and features each car has been made with. These only make sense in the context of the brand, like Turbo / GTS for Porsche and SVG for Lamborghini. Volkswagen even has model-specific performance designations such as the Golf GTI and the Jetta GLS.

Organization

Brand architecture aims to take a diverse set of products and organize them into a meaningful brand.

Large companies end up making a very diverse set of products. Over the decades, innovators have discovered new markets, found new uses for their machinery, and acquired other companies.

M&A results in a portfolio of products that vary significantly in use and in the people they appeal to. All of these products could be profitable businesses in their own right, so it would be foolish to stop producing them. It would be equally silly to believe they could all be marketed in the same way.

For example, Kimberly-Clark makes a wide variety of paper-based products. They make tissue paper, toilet paper, paper towels, diapers, pads, tampons, liners, and incontinence guards. These are all essential products and profitable businesses. The users of their products range from infants to the elderly, and the buyers of these products are both consumers and businesses. There is no way they should all be marketed under the same brand.

A company’s brand architecture organizes the entire product portfolio into sets that can be marketed under brands that make sense to the end customer.

The products are primarily sorted by the customer they are targetting, and secondarily by the need they fulfill. The products’ common elements under a brand present a brand promise: the benefit a customer comes to expect from the products from a brand.

For more information on brand promises, examples, and steps on how to write your own, check out our article. You won’t believe what Walmart tried to promise with their Neighborhood Market brand.

Let’s continue our Kimberly-Clarke example. KC diapers and wipes are marketed under the Huggies brand. The brand’s market is new parents, and the Huggies brand promise is enabling moms and dads to express their love by buying the most comfortable diapers for their little ones.

On the other side of the spectrum, Kimberly-Clarke makes adult care products that help people with bladder leaks and incontinence. Never are these products to be associated with diapers; the target market of middle-aged to elderly customers finds the comparison to diapers very degrading and demoralizing. As a result, Kimberly-Clarke markets these products under Poise and Depend. Both of these brands have a brand personality that is proud, noble, and assured. Both have a brand promise that enables adults to continue to live their lives fully with confidence and dignity.

No question organizing the products into these brands results in a more robust business for Kimberly-Clarke. Their brand architecture diversifies their companies and strengthens their connection with their customers.

Elements of Brand Architecture

Parent brand, sub-brand, product lines, and other elements in a brand hierarchy.

There are many ways brands can relate, and thus many ways to build a brand architecture. Different configurations may make more sense for a certain company, customer, or category.

Below we review all of the options available to brand managers when building their brand architecture. We go into more detail in BMB’s Overview of Brand Relationship Strategies.

Master Brand

A master brand is represented on all products and services a company sells. Usually, the master brand is the name of the company.

Examples: IBM, Google, FedEx

Umbrella Brand

An umbrella brand is used on many types of goods or services across product categories within a theme. One company can have multiple umbrella brands.

Examples: Cuisinart, Armorall, Tata

See BMB’s post about successful umbrella brands.

Parent Brand

A parent brand is a branching off point for multiple sub-brands that sell different products, sometimes in various categories.

Examples: Cadbury, Mr. Clean, Chevrolet

Endorsing Brand

An endorsing brand is similar to a master brand or umbrella brand, but the company’s brand is secondary to the product’s brand. An endorsing brand’s logo is usually in the top right corner of a logo or packaging design.

Examples: 3M, Christie, Nestle

Sub-Brand

A sub-brand adds to a parent brand’s name but differentiates it, so customers know to expect something different.

Examples: Samsung Galaxy, Toyota Prius, Virgin Galactic

See examples of successful sub-brands in BMB’s most successful post.

Product Line

A product line is a set of products in a single product category under one brand or sub-brand. The products in the line differ in scent, taste, size, packaging format, etc.

Examples: Mr. Clean Multi-Surface Cleaner, Wellness CORE® Pâté wet cat food, McDonald’s Happy Meal

Branded Technology

These are brands to an innovative material, design or process represented in multiple products.

Examples: 3M Thinsulate, Hyundai BlueDrive, Apple Retina Display

If you would like more to know more about each type’s strengths and weaknesses and understand related brands, check out our article: Overview of Brand Relationship Strategies.

Types of Brand Architecture

A focused (branded house) or a diversified (house of brands) portfolio of brands.

Every company’s portfolio is unique; it is shaped by its history, verticals, market, competition, and culture. They should be adaptable and responsive to the realities of the business environment.

But there are two schools of thought in brand management: ‘branded house’ and ‘house of brands.’ I do not find these models particularly valuable, but they are taught in business school and discussed in corporations, so I want you to be aware of them.

Branded House

Focused Brand Architecture

Examples: FedEx, IBM, Google, GE, Virgin, Tesla

A branded house is a company that focuses their effort towards a singular, strong brand.

A branded house markets all (or most) of the products/services under a monolithic brand. A branded house strategy makes the most use of the existing brand equity, and all goodwill accrues back to the brand. The brand name is usually the name of the company itself. The names of the sub-brands or products are descriptive (e.g., FedEx Freight or IBM Cloud.)

A single, broad-reaching brand works for some industries more than others. A tech giant may be able to effectively brand hundreds of pieces of software under the same brand. At the same time, a personal care company would be better served by breaking their offering into multiple targetted brands.

Benefits to a ‘branded house’ strategy:

- Simplicity

- Builds one powerful brand

- Greater brand awareness

Drawbacks to a ‘branded house’ strategy:

- Lack of specificity

- The broader the business is, the less meaningful the brand is

- Sensitive to public relations disasters

- Can’t market multiple brands in the same vertical

- Cant spin-out or sell brands

- Brands from mergers and acquisitions need to be rebranded into the company brand, losing their brand equity

The “branded house” strategy was popular from the end of the industrial revolution (1820s-1840s) to the mid 20th century (1950s – 1960s). Big organizations could dominate the means of production and the media and competed to be the largest and most influential.

Now, it is considered antiquated. There is no reason to stick to a single brand when two brands would better adapt to the market.

Smaller companies should use a “branded house” model to focus their efforts and build their brand awareness. But and small to medium-sized business (SMB) that offers products so diverse that they are considering multiple brands should consider focusing their efforts and capital on the businesses that are working well, and scrap the others.

House of Brands

Pluralistic Brand Architecture

Examples: Procter & Gamble, Unilever, The Kraft Heinz Company, Volkswagen

A house of brands or a pluralistic brand architecture comprises many brands, each focused on its market.

Companies that employ the house of brands strategy are free to market a product under whatever brand makes the most sense for the market or start a completely new brand. These companies don’t have to use the parent company’s name; they use a brand that speaks to the market’s needs, personality, and expectations.

The house of brands model is most effective in consumer packaged goods, such as food, cleaning products, and paper goods. A company’s expertise, intellectual property, and distribution channels can solve vastly different problems that necessitate different brands.

For example, The Clorox Company makes harsh, caustic drain cleaner and water purification systems. I don’t know about you, but I don’t want to think about poisonous chemicals when I am drinking purified water, so they shouldn’t both be marketed under the Clorox name. And they aren’t; the drain cleaner is called Liquid Plumr, and the water system is called Brita.

Benefits to a ‘house of brands’ strategy:

- Diversification of business and investments

- Brands specifically target their markets

- The company can be diversified and maintain meaningful brands

- Public relations disasters only affect one brand and business line

- Can have multiple brands in the same product category to appeal to different demographics

- Can liquidate brand equity by selling off brands

- Can acquire brands from other companies

Drawbacks to a ‘house of brands’ strategy:

- Very complicated

- Challenging to communicate

- Requires more investment in promotion/advertising to build brand awareness of all brands

Marketers and executives came around to the idea that not everything can or should be under one name in the mid-1900s. After Proctor & Gamble saw limitless success with the strategy, most modern corporations followed suit.

A pluralistic brand architecture enables corporations to spin out, sell, or trade brands because they aren’t linked to the parent company’s brand. For example, P&G sold the Duracell brand to Berkshire Hathaway Inc. for $2.9 billion in 2016. Selling a brand enables a company to turn its brand equity into cold-hard-cash if they need the capital for other businesses.

Now, nearly every business person will agree that the parent company’s name should have little to no impact on what brand to market a product under. The brand should fit the market, and trying to fit the market to the brand is a waste of resources.

Brand Architecture Strategies Are Never Binary

Companies are never strictly a “house of brands” or a “branded house.” Instead, a combination of both.

The difference between a “branded house” and a “house of brands” is often purely semantic. If you zoom out, any large organization is going to look like a “house of brands.” Google, which is often cited as the purest example of a “branded house,” is just one brand under Alphabet, Google’s parent company, runs eleven other brands, including DeepMind and Waymo.

Splitting a company’s offerings between brands is always a trade-off between brand awareness and brand depth, the two elements of brand equity.

It is undoubtedly easier to get a brand into the public consciousness when many offerings are marketed under a single name. Still, it may be too broadly defined to be meaningful to anyone. We call this loss of meaning brand dilution.

The most influential brands are the ones that have a clear and profound meaning to individual people, which often means the brand has it’s niche and is only relevant to a subset of people.

Conclusion: What Brand Architecture means for Brand Management

Brand Architecture is a crucial responsibility of executives and brand managers.

At its core, brand architecture is a set of decisions. The decisions are what brands should be used to market which types of products, and they align the efforts of R&D, product managers, marketers, and many others. These decisions are made by company executives and kept consistent by brand managers.

Executives make the decisions that define each and every brand that the company owns or licenses. These decisions are made using various criteria: vision, technology, brand equity, partners, market trends, forecasts, priorities, etc. The decisions that define the brand architecture need to be made by C-level executives because of the factors involved and to make sure the entire organization is aware and behind it.

It is up to the brand manager to make sure product and marketing decisions make sense in the context of the brand architecture. A brand manager may make up the diagrams and language used to communicate the brand architecture to product designers, marketers, and partners.

A brand manager should be looking for signals that the products make sense for their respective brands or if a product under the wrong brand is confusing the market. They should suggest which brand a product should be rebranded too, or if a new brand needs to be created.

If the brand architecture is flawed, and there is no way of making the product portfolio work with the brands as they are defined, then the brand manager needs to make suggestions for the executives to contemplate. The executives can only redefine the brands.

All of the efforts by the executives and the brand managers is to maintain and grow brand equity. Like any significant asset of the company (physical plant, intellectual property, etc.), there needs to be diligent management and reinvestment into the brand portfolio if it is to continue making a

Leave a Reply